Working for a Micro-Manager

Nearly everyone has had the experience of working for a micro-manager. Micro-management can range from asking for very detailed weekly status reports to reviewing and editing all outgoing emails. If you work for a micro-manager, it can look like your boss is the cause of your frustration and anger.

Nearly everyone has had the experience of working for a micro-manager. Micro-management can range from asking for very detailed weekly status reports to reviewing and editing all outgoing emails. If you work for a micro-manager, it can look like your boss is the cause of your frustration and anger.

Thank goodness that’s not true.

A few years ago, I was asked to coach a senior manager described by her boss as too emotional, defensive, and reactive. In retrospect, my first interaction with this client’s boss was a preview of what was to come and a significant factor in my client’s reactions. The boss had no time for a face-to-face meeting and began our introductory call with a lengthy description of her credentials and experience, including her status as a certified coach. When it came to discussing my client, most of what she had to offer was what she was doing to help her employee and suggestions of what I might do. She wanted to know about the tips and techniques I use.

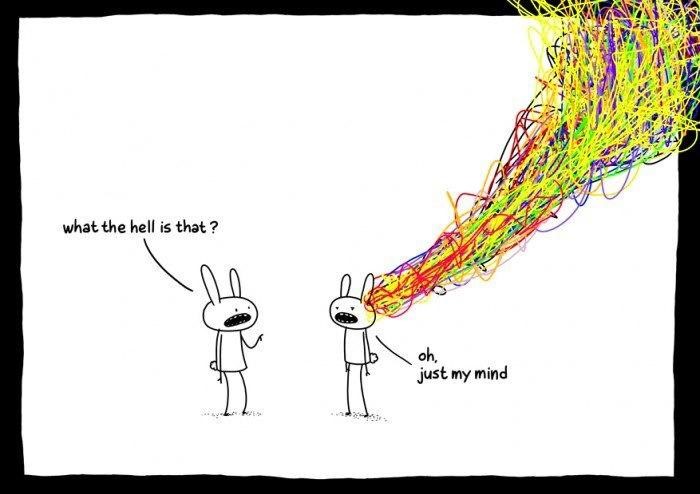

Nancy – my client – was a delightful, caring, and hard-working woman. She had significant experience in her field. Her 360 feedback report showed that she was respected and liked by her team. Oh, and she was absolutely what I call a “busy bee” – busy minded and preoccupied with a lot of how-am-I-doing thinking.

Sometimes clients exaggerate the more challenging aspects of their bosses’ behavior, so I was a bit surprised when Nancy showed me an email in which her boss criticized the font she used in her emails. There were comments about the content as well, but the font seemed to be the most egregious problem. Nancy’s boss also monitored her time and daily schedule to a degree not usually seen in Director-level work.

I would describe Nancy’s initial feeling state as frustrated, angry, and defensive. She cried as she told me about dealing with her boss and the admittedly unprofessional comments and advice she regularly received. Although this sounds like a complex and untenable situation, the good news is that there was only one thing Nancy needed to realize – no one has the power to make you feel anything. Not even your micro-managing, hypercritical, unprofessional boss.

Nancy has a teenage daughter, so it was easy to find an example to illustrate the inside-out nature of life. I asked her if she had ever tried to make her daughter feel better about some teenage angst or trauma. Oh yes, she said. And you love her very much and tried very hard, right? Yes. How did it work?

It didn’t.

That’s because the human mind doesn’t work that way. Because we are always creating our experience of life from the inside through the power of thought and consciousness, no one can make you feel better. Or worse. We feel our thinking about the world, not the circumstances we’re in or the people around us.

It took a bit of trial and error, but Nancy started to catch herself getting revved up by the things her boss said or did. She saw the shift of power – from the outside to the inside. She stopped over-reacting to her boss’s requests for info and was able to respond more effectively from a state of mental clarity as opposed to defensiveness. She stopped second-guessing herself and/or worrying about how her team was doing. Her mind quieted down. From a state of wisdom and common sense, she realized that she was pushing herself too hard and started making time for some self-care.

When she told me she was resuming her bi-monthly massages, I knew my work was done.

Her boss is still there, she hasn’t changed a bit. But Nancy can handle it better now that she’s seen the inside-out nature of life.