Mr. Spaghetti Head

If you met my coaching client, Parker, you’d probably wonder why he even needs a coach at all. An MIT PhD biochemist, Parker did his post doc work in a lab run by the founder of his current company. They do exciting work trying to find a cure for cancer. With his big genuine smile and way of connecting, people love Parker. He’s paid well and works in a hip company – and he’s not even 40.

If you met my coaching client, Parker, you’d probably wonder why he even needs a coach at all. An MIT PhD biochemist, Parker did his post doc work in a lab run by the founder of his current company. They do exciting work trying to find a cure for cancer. With his big genuine smile and way of connecting, people love Parker. He’s paid well and works in a hip company – and he’s not even 40.

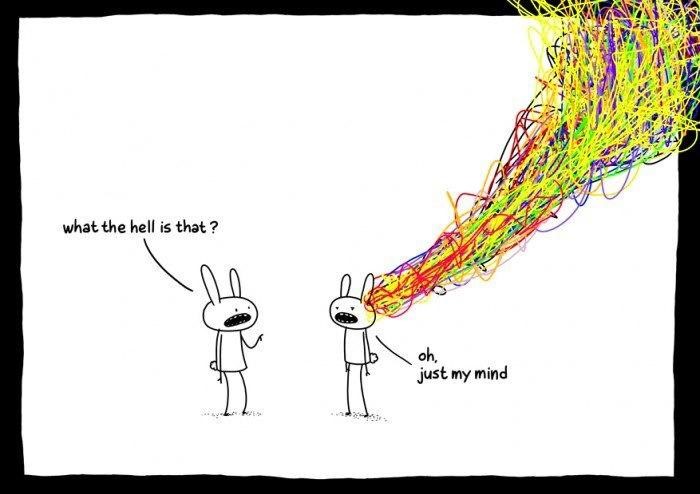

If things are going so well for him, what’s his problem? Spaghetti head.

Spaghetti head is shorthand for a picture I use with my clients.

The content of Parker’s spaghetti head was a whole lotta thinking about who he is and how he’s doing. He didn’t see it as ego and he didn’t see that it’s all made up.

Yes, everything we think about ourselves – the good, the bad, and the ugly – is made of thought. It’s thought, but it looks like the truth.

Parker is very fond of his knowledge. He believes he knows how things should be. He gets frustrated when people don’t do things correctly – especially people who are above him in the hierarchy. Furthermore, they aren’t making backpack zippers – they’re trying to cure cancer!

He’s a pretty good listener, and because he has the reputation for speaking truth to power, people come to him to complain about things. And of course, he readily jumps in the soup and takes on their frustration.

Parker was burning out when I met him. When you believe your frustration is coming from your circumstances and other people, you don’t have many options. He didn’t want to move to another company, but he didn’t see any other way out.

Luckily, he was up for seeing something different about how life works. He read everything I gave him, watched TED talks, and completely identified with Spaghetti Head. He began noticing when he was starting to get caught up in a reaction of churning thoughts and pulled back. Leaning into the thought storm stopped making sense to him.

People, of course, noticed the change in his behavior, which initially presented another challenge. His colleagues said “Hey, what’s wrong with you? Are you quitting? How come you’re so quiet?” Admittedly, it was a significant shift because at first, he didn’t know what to do, other than get out of his reaction by trying to settle himself down. It took time for him to be able to re-engage from a more settled state of mind. But he did.

Here’s what he realized:

- His frustration was coming from his own thinking, not the situation.

- He was not effective when he was caught up in a reaction.

Towards the end of our coaching engagement, there was a reorganization in the company and one of his colleagues quit. When he came home that night and told his wife she said, “So is this how tonight’s going to go?” because his usual MO was to spend the evening complaining and being frustrated. But this time, it was different. His troublesome thoughts dissipated and he was able to have an enjoyable evening with his family.

Yeah, curing cancer is a pretty important job – but so is being a husband and a Dad.

When I was 16, my Dad bought me a car. Not just any car, a red 1966 Chevy Impala SS ragtop with a 425HP V8 engine. A fierce American muscle car with a manual transmission and heavy duty clutch.

When I was 16, my Dad bought me a car. Not just any car, a red 1966 Chevy Impala SS ragtop with a 425HP V8 engine. A fierce American muscle car with a manual transmission and heavy duty clutch.